The TPSPLINE Procedure

The theoretical foundations for the thin-plate smoothing spline are described in Duchon (1976, 1977) and Meinguet (1979). Further results and applications are given in: Wahba and Wendelberger (1980); Hutchinson and Bischof (1983); Seaman and Hutchinson (1985).

Suppose that ![]() is a space of functions whose partial derivatives of total order m are in

is a space of functions whose partial derivatives of total order m are in ![]() , where

, where ![]() is the domain of

is the domain of ![]() .

.

Now, consider the data model

where ![]() .

.

Using the notation from the section Penalized Least Squares Estimation, for a fixed ![]() , estimate f by minimizing the penalized least squares function

, estimate f by minimizing the penalized least squares function

![]() is the penalty term to enforce smoothness on f. There are several ways to define

is the penalty term to enforce smoothness on f. There are several ways to define ![]() . For the thin-plate smoothing spline, with

. For the thin-plate smoothing spline, with ![]() of dimension d, define

of dimension d, define ![]() as

as

where ![]() . Under this definition,

. Under this definition, ![]() gives zero penalty to some functions. The space that is spanned by the set of polynomials that contribute zero penalty is

called the polynomial space. The dimension of the polynomial space M is a function of dimension d and order m of the smoothing penalty,

gives zero penalty to some functions. The space that is spanned by the set of polynomials that contribute zero penalty is

called the polynomial space. The dimension of the polynomial space M is a function of dimension d and order m of the smoothing penalty, ![]() .

.

Given the condition that ![]() , the function that minimizes the penalized least squares criterion has the form

, the function that minimizes the penalized least squares criterion has the form

where ![]() and

and ![]() are vectors of coefficients to be estimated. The M functions

are vectors of coefficients to be estimated. The M functions ![]() are linearly independent polynomials that span the space of functions for which

are linearly independent polynomials that span the space of functions for which ![]() is zero. The basis functions

is zero. The basis functions ![]() are defined as

are defined as

When d = 2 and m = 2, then ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() .

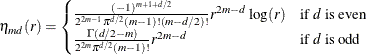

. ![]() is as follows:

is as follows:

For the sake of simplicity, the formulas and equations that follow assume m = 2. See Wahba (1990) and Bates et al. (1987) for more details.

Duchon (1976) showed that ![]() can be represented as

can be represented as

where ![]() for d = 2. For derivations of

for d = 2. For derivations of ![]() for other values of d, see Villalobos and Wahba (1987).

for other values of d, see Villalobos and Wahba (1987).

If you define ![]() with elements

with elements ![]() and

and ![]() with elements

with elements ![]() , the goal is to find vectors of coefficients

, the goal is to find vectors of coefficients ![]() and

and ![]() that minimize

that minimize

A unique solution is guaranteed if the matrix ![]() is of full rank and

is of full rank and ![]() .

.

If ![]() and

and ![]() , the expression for

, the expression for ![]() becomes

becomes

The coefficients ![]() and

and ![]() can be obtained by solving

can be obtained by solving

To compute ![]() and

and ![]() , let the QR decomposition of

, let the QR decomposition of ![]() be

be

where ![]() is an orthogonal matrix and

is an orthogonal matrix and ![]() is an upper triangular, with

is an upper triangular, with ![]() (Dongarra et al., 1979).

(Dongarra et al., 1979).

Since ![]() ,

, ![]() must be in the column space of

must be in the column space of ![]() . Therefore,

. Therefore, ![]() can be expressed as

can be expressed as ![]() for a vector

for a vector ![]() . Substituting

. Substituting ![]() into the preceding equation and multiplying through by

into the preceding equation and multiplying through by ![]() gives

gives

or

The coefficient ![]() can be obtained by solving

can be obtained by solving

The influence matrix ![]() is defined as

is defined as

and has the form

Similar to the regression case, if you consider the trace of ![]() as the degrees of freedom for the model and the trace of

as the degrees of freedom for the model and the trace of ![]() as the degrees of freedom for the error, the estimate

as the degrees of freedom for the error, the estimate ![]() can be represented as

can be represented as

where ![]() is the residual sum of squares. Theoretical properties of these estimates have not yet been published. However, good numerical

results in simulation studies have been described by several authors. For more information, see O’Sullivan and Wong (1987); Nychka (1986a, 1986b, 1988); Hall and Titterington (1987).

is the residual sum of squares. Theoretical properties of these estimates have not yet been published. However, good numerical

results in simulation studies have been described by several authors. For more information, see O’Sullivan and Wong (1987); Nychka (1986a, 1986b, 1988); Hall and Titterington (1987).

Viewing the spline model as a Bayesian model, Wahba (1983) proposed Bayesian confidence intervals for smoothing spline estimates as

where ![]() is the ith diagonal element of the

is the ith diagonal element of the ![]() matrix and

matrix and ![]() is the

is the ![]() quantile of the standard normal distribution. The confidence intervals are interpreted as intervals “across the function” as opposed to pointwise intervals.

quantile of the standard normal distribution. The confidence intervals are interpreted as intervals “across the function” as opposed to pointwise intervals.

For SCORE data sets, the hat matrix ![]() is not available. To compute the Bayesian confidence interval for a new point

is not available. To compute the Bayesian confidence interval for a new point ![]() , let

, let

and let ![]() be an

be an ![]() vector with ith entry

vector with ith entry

When d = 2 and m = 2, ![]() is computed with

is computed with

![]() is a vector of evaluations of

is a vector of evaluations of ![]() by the polynomials that span the functional space where

by the polynomials that span the functional space where ![]() is zero. The details for

is zero. The details for ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() are discussed in the previous section. Wahba (1983) showed that the Bayesian posterior variance of

are discussed in the previous section. Wahba (1983) showed that the Bayesian posterior variance of ![]() satisfies

satisfies

where

Suppose that you fit a spline estimate that consists of a true function f and a random error term ![]() to experimental data. In repeated experiments, it is likely that about

to experimental data. In repeated experiments, it is likely that about ![]() of the confidence intervals cover the corresponding true values, although some values are covered every time and other values

are not covered by the confidence intervals most of the time. This effect is more pronounced when the true surface or surface

has small regions of particularly rapid change.

of the confidence intervals cover the corresponding true values, although some values are covered every time and other values

are not covered by the confidence intervals most of the time. This effect is more pronounced when the true surface or surface

has small regions of particularly rapid change.

The quantity ![]() is called the smoothing parameter, which controls the balance between the goodness of fit and the smoothness of the final

estimate.

is called the smoothing parameter, which controls the balance between the goodness of fit and the smoothness of the final

estimate.

A large ![]() heavily penalizes the mth derivative of the function, thus forcing

heavily penalizes the mth derivative of the function, thus forcing ![]() close to 0. A small

close to 0. A small ![]() places less of a penalty on rapid change in

places less of a penalty on rapid change in ![]() , resulting in an estimate that tends to interpolate the data points.

, resulting in an estimate that tends to interpolate the data points.

The smoothing parameter greatly affects the analysis, and it should be selected with care. One method is to perform several

analyses with different values for ![]() and compare the resulting final estimates.

and compare the resulting final estimates.

A more objective way to select the smoothing parameter ![]() is to use the “leave-out-one” cross validation function, which is an approximation of the predicted mean squares error. A generalized version of the leave-out-one

cross validation function is proposed by Wahba (1990) and is easy to calculate. This generalized cross validation (GCV) function is defined as

is to use the “leave-out-one” cross validation function, which is an approximation of the predicted mean squares error. A generalized version of the leave-out-one

cross validation function is proposed by Wahba (1990) and is easy to calculate. This generalized cross validation (GCV) function is defined as

The justification for using the GCV function to select ![]() relies on asymptotic theory. Thus, you cannot expect good results for very small sample sizes or when there is not enough

information in the data to separate the model from the error component. Simulation studies suggest that for independent and

identically distributed Gaussian noise, you can obtain reliable estimates of

relies on asymptotic theory. Thus, you cannot expect good results for very small sample sizes or when there is not enough

information in the data to separate the model from the error component. Simulation studies suggest that for independent and

identically distributed Gaussian noise, you can obtain reliable estimates of ![]() for n greater than 25 or 30. Note that, even for large values of n (say,

for n greater than 25 or 30. Note that, even for large values of n (say, ![]() ), in extreme Monte Carlo simulations there might be a small percentage of unwarranted extreme estimates in which

), in extreme Monte Carlo simulations there might be a small percentage of unwarranted extreme estimates in which ![]() or

or ![]() (Wahba, 1983). Generally, if

(Wahba, 1983). Generally, if ![]() is known to within an order of magnitude, the occasional extreme case can be readily identified. As n gets larger, the effect becomes weaker.

is known to within an order of magnitude, the occasional extreme case can be readily identified. As n gets larger, the effect becomes weaker.

The GCV function is fairly robust against nonhomogeneity of variances and non-Gaussian errors (Villalobos and Wahba, 1987). Andrews (1988) has provided favorable theoretical results when variances are unequal. However, this selection method is likely to give unsatisfactory results when the errors are highly correlated.

The GCV value might be suspect when ![]() is extremely small because computed values might become indistinguishable from zero. In practice, calculations with

is extremely small because computed values might become indistinguishable from zero. In practice, calculations with ![]() or

or ![]() near 0 can cause numerical instabilities that result in an unsatisfactory solution. Simulation studies have shown that a

near 0 can cause numerical instabilities that result in an unsatisfactory solution. Simulation studies have shown that a

![]() with

with ![]() is small enough that the final estimate based on this

is small enough that the final estimate based on this ![]() almost interpolates the data points. A GCV value based on a

almost interpolates the data points. A GCV value based on a ![]() might not be accurate.

might not be accurate.