The VARMAX Procedure

- Overview

-

Getting Started

-

Syntax

-

Details

Missing ValuesVARMAX ModelDynamic Simultaneous Equations ModelingImpulse Response FunctionForecastingTentative Order SelectionVAR and VARX ModelingBayesian VAR and VARX ModelingVARMA and VARMAX ModelingModel Diagnostic ChecksCointegrationVector Error Correction ModelingI(2) ModelMultivariate GARCH ModelingOutput Data SetsOUT= Data SetOUTEST= Data SetOUTHT= Data SetOUTSTAT= Data SetPrinted OutputODS Table NamesODS GraphicsComputational Issues

Missing ValuesVARMAX ModelDynamic Simultaneous Equations ModelingImpulse Response FunctionForecastingTentative Order SelectionVAR and VARX ModelingBayesian VAR and VARX ModelingVARMA and VARMAX ModelingModel Diagnostic ChecksCointegrationVector Error Correction ModelingI(2) ModelMultivariate GARCH ModelingOutput Data SetsOUT= Data SetOUTEST= Data SetOUTHT= Data SetOUTSTAT= Data SetPrinted OutputODS Table NamesODS GraphicsComputational Issues -

Examples

- References

- Simple Impulse Response Function (IMPULSE=SIMPLE Option)

- Accumulated Impulse Response Function (IMPULSE=ACCUM Option)

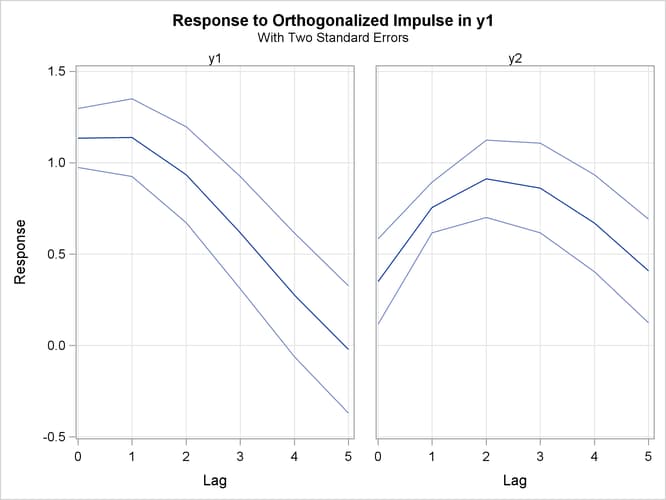

- Orthogonalized Impulse Response Function (IMPULSE=ORTH Option)

- Impulse Response of Transfer Function (IMPULSX=SIMPLE Option)

- Impulse Response of Transfer Function (IMPULSX=ACCUM Option)

The VARMAX(![]() ,

,![]() ,

,![]() ) model has a convergent representation

) model has a convergent representation

where ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

The elements of the matrices ![]() from the operator

from the operator ![]() , called the impulse response, can be interpreted as the impact that a shock in one variable has on another variable. Let

, called the impulse response, can be interpreted as the impact that a shock in one variable has on another variable. Let

![]() be the

be the ![]() element of

element of ![]() at lag

at lag ![]() , where

, where ![]() is the index for the impulse variable, and

is the index for the impulse variable, and ![]() is the index for the response variable (impulse

is the index for the response variable (impulse ![]() response). For instance,

response). For instance, ![]() is an impulse response to

is an impulse response to ![]() , and

, and ![]() is an impulse response to

is an impulse response to ![]() .

.

The accumulated impulse response function is the cumulative sum of the impulse response function, ![]() .

.

The MA representation of a VARMA(![]() ,

,![]() ) model with a standardized white noise innovation process offers another way to interpret a VARMA(

) model with a standardized white noise innovation process offers another way to interpret a VARMA(![]() ,

,![]() ) model. Since

) model. Since ![]() is positive-definite, there is a lower triangular matrix

is positive-definite, there is a lower triangular matrix ![]() such that

such that ![]() . The alternate MA representation of a VARMA(

. The alternate MA representation of a VARMA(![]() ,

,![]() ) model is written as

) model is written as

where ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() .

.

The elements of the matrices ![]() , called the orthogonal impulse response, can be interpreted as the effects of the components of the standardized shock process

, called the orthogonal impulse response, can be interpreted as the effects of the components of the standardized shock process ![]() on the process

on the process ![]() at lag

at lag ![]() .

.

The coefficient matrix ![]() from the transfer function operator

from the transfer function operator ![]() can be interpreted as the effects that changes in the exogenous variables

can be interpreted as the effects that changes in the exogenous variables ![]() have on the output variable

have on the output variable ![]() at lag

at lag ![]() ; it is called an impulse response matrix in the transfer function.

; it is called an impulse response matrix in the transfer function.

The accumulated impulse response in the transfer function is the cumulative sum of the impulse response in the transfer function,

![]() .

.

The asymptotic distributions of the impulse functions can be seen in the section VAR and VARX Modeling.

The following statements provide the impulse response and the accumulated impulse response in the transfer function for a VARX(1,0) model.

proc varmax data=grunfeld plot=impulse;

model y1-y3 = x1 x2 / p=1 lagmax=5

printform=univariate

print=(impulsx=(all) estimates);

run;

In Figure 35.26, the variables ![]() and

and ![]() are impulses and the variables

are impulses and the variables ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() are responses. You can read the table matching the pairs of

are responses. You can read the table matching the pairs of ![]() such as

such as ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . In the pair of

. In the pair of ![]() , you can see the long-run responses of

, you can see the long-run responses of ![]() to an impulse in

to an impulse in ![]() (the values are 1.69281, 0.35399, 0.09090, and so on for lag 0, lag 1, lag 2, and so on, respectively).

(the values are 1.69281, 0.35399, 0.09090, and so on for lag 0, lag 1, lag 2, and so on, respectively).

Figure 35.26: Impulse Response in Transfer Function (IMPULSX= Option)

| Simple Impulse Response of Transfer Function by Variable |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable Response\Impulse |

Lag | x1 | x2 |

| y1 | 0 | 1.69281 | -0.00859 |

| 1 | 0.35399 | 0.01727 | |

| 2 | 0.09090 | 0.00714 | |

| 3 | 0.05136 | 0.00214 | |

| 4 | 0.04717 | 0.00072 | |

| 5 | 0.04620 | 0.00040 | |

| y2 | 0 | -6.09850 | 2.57980 |

| 1 | -5.15484 | 0.45445 | |

| 2 | -3.04168 | 0.04391 | |

| 3 | -2.23797 | -0.01376 | |

| 4 | -1.98183 | -0.01647 | |

| 5 | -1.87415 | -0.01453 | |

| y3 | 0 | -0.02317 | -0.01274 |

| 1 | 1.57476 | -0.01435 | |

| 2 | 1.80231 | 0.00398 | |

| 3 | 1.77024 | 0.01062 | |

| 4 | 1.70435 | 0.01197 | |

| 5 | 1.63913 | 0.01187 | |

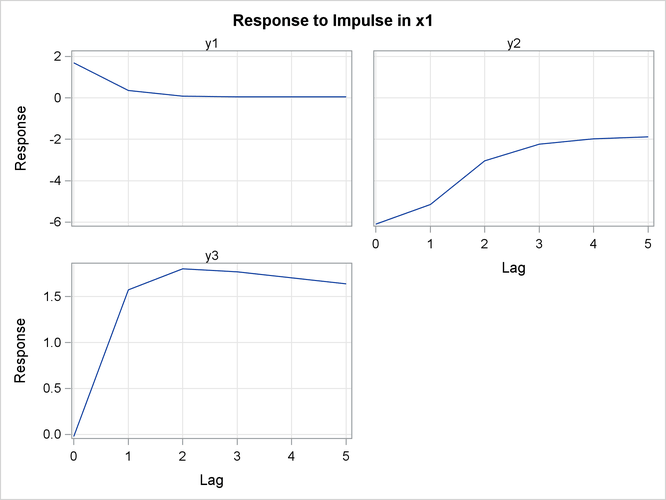

Figure 35.27 shows the responses of ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() to a forecast error impulse in

to a forecast error impulse in ![]() .

.

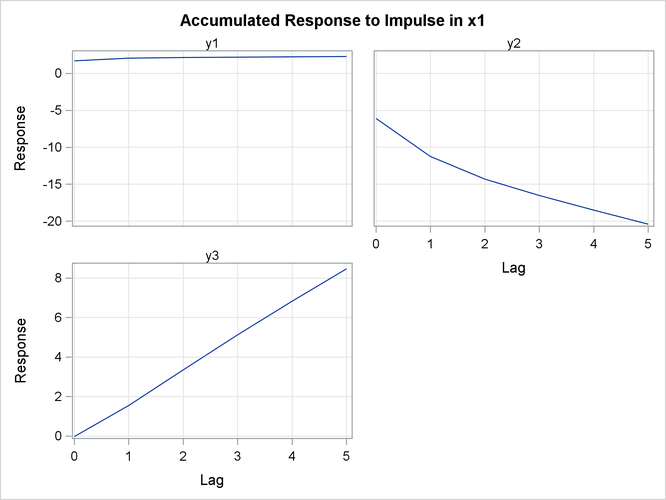

Figure 35.28 shows the accumulated impulse response in transfer function.

Figure 35.28: Accumulated Impulse Response in Transfer Function (IMPULSX= Option)

| Accumulated Impulse Response of Transfer Function by Variable |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable Response\Impulse |

Lag | x1 | x2 |

| y1 | 0 | 1.69281 | -0.00859 |

| 1 | 2.04680 | 0.00868 | |

| 2 | 2.13770 | 0.01582 | |

| 3 | 2.18906 | 0.01796 | |

| 4 | 2.23623 | 0.01867 | |

| 5 | 2.28243 | 0.01907 | |

| y2 | 0 | -6.09850 | 2.57980 |

| 1 | -11.25334 | 3.03425 | |

| 2 | -14.29502 | 3.07816 | |

| 3 | -16.53299 | 3.06440 | |

| 4 | -18.51482 | 3.04793 | |

| 5 | -20.38897 | 3.03340 | |

| y3 | 0 | -0.02317 | -0.01274 |

| 1 | 1.55159 | -0.02709 | |

| 2 | 3.35390 | -0.02311 | |

| 3 | 5.12414 | -0.01249 | |

| 4 | 6.82848 | -0.00052 | |

| 5 | 8.46762 | 0.01135 | |

Figure 35.29 shows the accumulated responses of ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() to a forecast error impulse in

to a forecast error impulse in ![]() .

.

The following statements provide the impulse response function, the accumulated impulse response function, and the orthogonalized impulse response function with their standard errors for a VAR(1) model. Parts of the VARMAX procedure output are shown in Figure 35.30, Figure 35.32, and Figure 35.34.

proc varmax data=simul1 plot=impulse;

model y1 y2 / p=1 noint lagmax=5

print=(impulse=(all))

printform=univariate;

run;

Figure 35.30 is the output in a univariate format associated with the PRINT=(IMPULSE=) option for the impulse response function. The keyword

STD stands for the standard errors of the elements. The matrix in terms of the lag 0 does not print since it is the identity.

In Figure 35.30, the variables ![]() and

and ![]() of the first row are impulses, and the variables

of the first row are impulses, and the variables ![]() and

and ![]() of the first column are responses. You can read the table matching the

of the first column are responses. You can read the table matching the ![]() pairs, such as

pairs, such as ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . For example, in the pair of

. For example, in the pair of ![]() at lag 3, the response is 0.8055. This represents the impact on y1 of one-unit change in

at lag 3, the response is 0.8055. This represents the impact on y1 of one-unit change in ![]() after 3 periods. As the lag gets higher, you can see the long-run responses of

after 3 periods. As the lag gets higher, you can see the long-run responses of ![]() to an impulse in itself.

to an impulse in itself.

Figure 35.30: Impulse Response Function (IMPULSE= Option)

| Simple Impulse Response by Variable | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable Response\Impulse |

Lag | y1 | y2 |

| y1 | 1 | 1.15977 | -0.51058 |

| STD | 0.05508 | 0.05898 | |

| 2 | 1.06612 | -0.78872 | |

| STD | 0.10450 | 0.10702 | |

| 3 | 0.80555 | -0.84798 | |

| STD | 0.14522 | 0.14121 | |

| 4 | 0.47097 | -0.73776 | |

| STD | 0.17191 | 0.15864 | |

| 5 | 0.14315 | -0.52450 | |

| STD | 0.18214 | 0.16115 | |

| y2 | 1 | 0.54634 | 0.38499 |

| STD | 0.05779 | 0.06188 | |

| 2 | 0.84396 | -0.13073 | |

| STD | 0.08481 | 0.08556 | |

| 3 | 0.90738 | -0.48124 | |

| STD | 0.10307 | 0.09865 | |

| 4 | 0.78943 | -0.64856 | |

| STD | 0.12318 | 0.11661 | |

| 5 | 0.56123 | -0.65275 | |

| STD | 0.14236 | 0.13482 | |

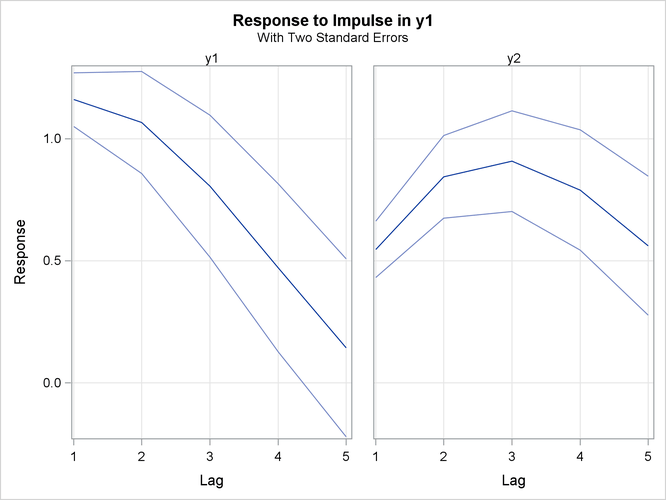

Figure 35.31 shows the responses of ![]() and

and ![]() to a forecast error impulse in

to a forecast error impulse in ![]() with two standard errors.

with two standard errors.

Figure 35.32 is the output in a univariate format associated with the PRINT=(IMPULSE=) option for the accumulated impulse response function. The matrix in terms of the lag 0 does not print since it is the identity.

Figure 35.32: Accumulated Impulse Response Function (IMPULSE= Option)

| Accumulated Impulse Response by Variable | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable Response\Impulse |

Lag | y1 | y2 |

| y1 | 1 | 2.15977 | -0.51058 |

| STD | 0.05508 | 0.05898 | |

| 2 | 3.22589 | -1.29929 | |

| STD | 0.21684 | 0.22776 | |

| 3 | 4.03144 | -2.14728 | |

| STD | 0.52217 | 0.53649 | |

| 4 | 4.50241 | -2.88504 | |

| STD | 0.96922 | 0.97088 | |

| 5 | 4.64556 | -3.40953 | |

| STD | 1.51137 | 1.47122 | |

| y2 | 1 | 0.54634 | 1.38499 |

| STD | 0.05779 | 0.06188 | |

| 2 | 1.39030 | 1.25426 | |

| STD | 0.17614 | 0.18392 | |

| 3 | 2.29768 | 0.77302 | |

| STD | 0.36166 | 0.36874 | |

| 4 | 3.08711 | 0.12447 | |

| STD | 0.65129 | 0.65333 | |

| 5 | 3.64834 | -0.52829 | |

| STD | 1.07510 | 1.06309 | |

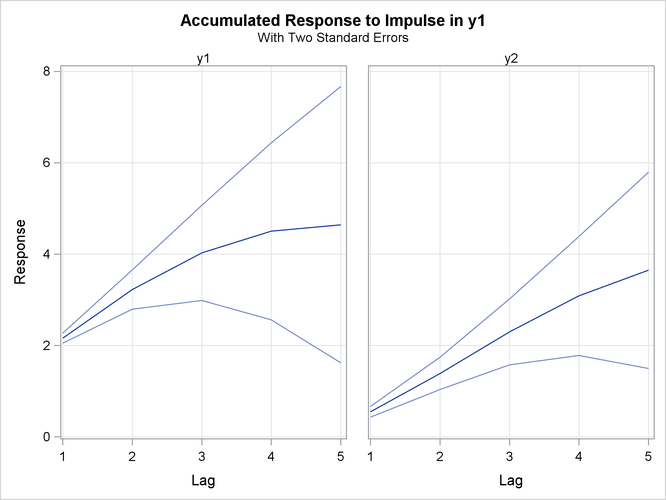

Figure 35.33 shows the accumulated responses of ![]() and

and ![]() to a forecast error impulse in

to a forecast error impulse in ![]() with two standard errors.

with two standard errors.

Figure 35.34 is the output in a univariate format associated with the PRINT=(IMPULSE=) option for the orthogonalized impulse response

function. The two right-hand side columns, ![]() and

and ![]() , represent the

, represent the ![]() and

and ![]() variables. These are the impulses variables. The left-hand side column contains responses variables,

variables. These are the impulses variables. The left-hand side column contains responses variables, ![]() and

and ![]() . You can read the table by matching the

. You can read the table by matching the ![]() pairs such as

pairs such as ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() .

.

Figure 35.34: Orthogonalized Impulse Response Function (IMPULSE= Option)

| Orthogonalized Impulse Response by Variable | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable Response\Impulse |

Lag | y1 | y2 |

| y1 | 0 | 1.13523 | 0.00000 |

| STD | 0.08068 | 0.00000 | |

| 1 | 1.13783 | -0.58120 | |

| STD | 0.10666 | 0.14110 | |

| 2 | 0.93412 | -0.89782 | |

| STD | 0.13113 | 0.16776 | |

| 3 | 0.61756 | -0.96528 | |

| STD | 0.15348 | 0.18595 | |

| 4 | 0.27633 | -0.83981 | |

| STD | 0.16940 | 0.19230 | |

| 5 | -0.02115 | -0.59705 | |

| STD | 0.17432 | 0.18830 | |

| y2 | 0 | 0.35016 | 1.13832 |

| STD | 0.11676 | 0.08855 | |

| 1 | 0.75503 | 0.43824 | |

| STD | 0.06949 | 0.10937 | |

| 2 | 0.91231 | -0.14881 | |

| STD | 0.10553 | 0.13565 | |

| 3 | 0.86158 | -0.54780 | |

| STD | 0.12266 | 0.14825 | |

| 4 | 0.66909 | -0.73827 | |

| STD | 0.13305 | 0.15846 | |

| 5 | 0.40856 | -0.74304 | |

| STD | 0.14189 | 0.16765 | |

In Figure 35.4, there is a positive correlation between ![]() and

and ![]() . Therefore, shock in

. Therefore, shock in ![]() can be accompanied by a shock in

can be accompanied by a shock in ![]() in the same period. For example, in the pair of

in the same period. For example, in the pair of ![]() , you can see the long-run responses of

, you can see the long-run responses of ![]() to an impulse in

to an impulse in ![]() .

.

Figure 35.35 shows the orthogonalized responses of ![]() and

and ![]() to a forecast error impulse in

to a forecast error impulse in ![]() with two standard errors.

with two standard errors.